Enthusiasm and passion

The link between two commonly used but barely unravelled concepts

Enthusiasm and passion are words that are often used, both in daily life and in a professional environment. For example, companies look for enthusiastic employees with a passion for their field. And yet scientific research into enthusiasm and passion is limited. This article takes a closer look at these concepts and outlines their mutual relationship based on insights from science and business. The insights are then translated into practical applications. But let’s start with a short description of the two concepts.

Photo by Randalyn Hill on Unsplash

Passion

One of the few scientists who has engaged in research into passion is Professor Robert J. Vallerand from the University of Quebec. He defines passion as a strong inclination toward a self-defining activity that people like (or even love), find important, and in which they invest time and energy (Vallerand et al., 2003). It is therefore an essential part of a person’s identity. People see themselves as musicians or footballers as a result of the passion they feel for a specific activity. Vallerand distinguishes between two forms of passion (Vallerand et al., 2013). Harmonious passion originates in an autonomous and balanced way from within the person. This form of passion is important to the person, but there is no question of an irresistible urge. This is in contrast to obsessive passion. The latter form of passion often arises when there is an unhealthy internal or external pressure to perform. Poor performance is taken personally and an obsessive need to engage in the activity develops. Vallerand shows in various studies of students and athletes that harmonious passion in particular leads to sustained performance, good relationships, flow and well-being. Obsessive passion, on the other hand, is often accompanied by destructive behaviour, isolation and anxiety (Vallerand et al., 2013). When I talk about passion in the rest of the article, I am referring to harmonious passion, unless otherwise indicated.

Enthusiasm

Scientific research into enthusiasm is even harder to find. Positive psychology does pay attention to related themes such as flow and engagement, but enthusiasm still appears to be virgin territory in the academic world. Most of the statements I make here are therefore based on business research and personal experiences from training courses and consultancy work for organisations. In order to achieve a clear-cut delineation, I would like to propose the following definition of enthusiasm: “Enthusiasm is the positive excitement experienced when a person is affected by something or someone. It also creates a need to share and has a contagious effect on other people.” Enthusiasm therefore manifests itself explicitly in the moment and can also be observed in physical terms. There is an alertness, an eagerness, a twinkle in the eye. It’s as if something is awakening. The tendency to share enthusiasm is also striking, and this is very noticeable in children. If they have seen something that excites them, they are itching to share it. Adults who come home enthusiastic also feel this need. It even feels frustrating when no one is at home at that moment. Fortunately, these days we can call someone or share stories online. On social media, it’s easy to see how strong the need is to share enthusiasm. In fact, people share more positive messages online than negative ones (Ferrara, E. Yang, Z. 2015). The final characteristic of enthusiasm, which is contained in the definition, is its contagious nature. Like positive and negative emotions, enthusiasm is infectious. An enthusiastic colleague can set the mood and waves of enthusiasm can sweep through a crowd.

Enthusiasm as dowsing rod

Unlike enthusiasm, a passion can be latent. It’s only when someone is confronted with the activity in question that the passion manifests itself. Sometimes this passion is ignited at an early age, as in the case of Dutch racing driver Max Verstappen, who followed in the footsteps of his father Jos Verstappen when he was very young. Many people don’t find their calling until later. Some people spend their whole lives searching or just stumble upon it unexpectedly. When a passion like this manifests itself, chances are it is accompanied by enthusiasm. Because this passion comes from within, it can be interpreted as harmonious passion. Enthusiasm is like a dowsing rod for finding latent passion; it’s like an invisible hand that gives direction to our lives. In a large part of the world, people are free to make their own choices, after all, when it comes to partner, friends, study, job, holiday destinations, products and so on. A choice that is accompanied by enthusiasm is intuitively seen as a “good” decision. Without enthusiasm, there is either a forced choice or indifference. In both cases, intrinsic motivation is lacking and this makes the choice less likely to turn out well (Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L., 2000).

Practical application

In organisations, employees have not always chosen their positions based on enthusiasm. The job is often a financial necessity and many employees have limited say in the work they do. This can lead to an absence of passion or to obsessive passion (passion due to external pressure or necessity). However, in organisations where there is room to follow personal enthusiasm, employees are more likely to work from intrinsic motivation. This harmonious passion leads to better performance, less illness, better interpersonal relationships, and increased well-being (Vallerand et al., 2013). Over the years, I have seen hundreds of employees from various companies undergo training on customer and employee enthusiasm. In this two-day “Superpromoter Academy”, participants are challenged, among other things, to delve into their own enthusiasm, both in their private life and at work. This makes it clear where their passion lies and whether someone is doing the right job. They then look for a way to give these passions more space. Many of them go looking for other work as a result. Within a year, a significant number of them have found another job or have been able to combine passion and work in a different way. For instance, by taking on an additional task within the company as a photographer, by organising events or doing voluntary work. The results are very promising. Most of the more than 700 participants worldwide who have followed the training are enthusiastic afterwards and recognise its practical usefulness. The focus on enthusiasm releases a great deal. Anna Francken, photographer and employed at the Volksbank: “I felt my heart catch fire again”. These findings appear to align well with research that shows a positive effect between the extent to which people are allowed to use their signature strengths and the extent to which they experience harmonious passion (Forest et al. 2012). The result is better performance and greater well-being.

Keeping the fire burning

Once the passion has been found, it is still a challenge to keep it burning. Where passion can be seen as the fire, enthusiasm can be described as a spark. The enthusiasm has ignited the passion. But once the fire has been lit, it doesn’t stay burning by itself. Passion needs to be refuelled each time with inspiration and encouragement. In practice, we see that people only manage to maintain their enthusiasm for a certain activity if they surround themselves with others who share their passion (inspiration) and if they experience positive appreciation from their surroundings (encouragement). This last point can be linked to research into flow. Research by Csikszentmihalyi demonstrated that people need feedback to get into flow (Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1991). Without feedback, it comes to a dead end. The same goes for enthusiasm. If enthusiasm does not get a response, it fades into the background. It’s like telling a joke but nobody laughs. Not much chance of you telling this joke again. In organisations, employees lack positive feedback in particular. Most systems in an organisation, such as quality systems, performance appraisals and complaint handling, focus on problems. From these mechanisms, employees receive mainly negative feedback. Negative feedback is important for improvement, and it can even lead to flow if used properly, but one-sided negative feedback leads to a decline in enthusiasm in the long run. Positive feedback is particularly important when it comes to enthusiasm concerning a personal passion. The person identifies strongly with these activities and is therefore extra vulnerable. Positive feedback on activities undertaken from a personal passion fuels enthusiasm while negative feedback or indifference can kill the enthusiasm. In an environment where there is considerable focus on sharing positive stories, expressing appreciation and giving compliments, it’s easier to hold on to working from passion, as a result.

Practical application

In the aforementioned training courses on customer and employee enthusiasm, the importance of positive feedback is emphasised. In addition, they benefit greatly from insights and methodology originating from positive psychology. Employees are encouraged to express their appreciation to colleagues, share positive stories and give compliments. It is important that the appreciation is sincere – it shouldn’t just be a gimmick. When people take a moment to reflect on the achievements of the colleagues around them and the help they receive on a daily basis, they become more aware of the positive actions of their colleagues. The next step is to show their appreciation. This is particularly important when colleagues place themselves in a vulnerable position, by showing something of their passion.

These insights are also useful in social-media training. Many organisations would like to see employees share more positive stories about their work online. When we look at the situation at the start of a training course, we almost always find a few employees who, from harmonious passion, have already taken the lead and are sharing their stories. When these employees post a blog about an event they organised or about a subject within their field of work that appeals to them, we generally see few reactions. If the blog is shared on Twitter or Linkedin, it gets at most a few likes or retweets, even though there are often thousands of people working for such an organisation. By making people aware that every like, retweet or positive reaction is experienced as encouragement, complimentary behaviour can be stimulated. This makes it easier for the frontrunners to maintain their enthusiasm and lowers the threshold for colleagues to follow their example.

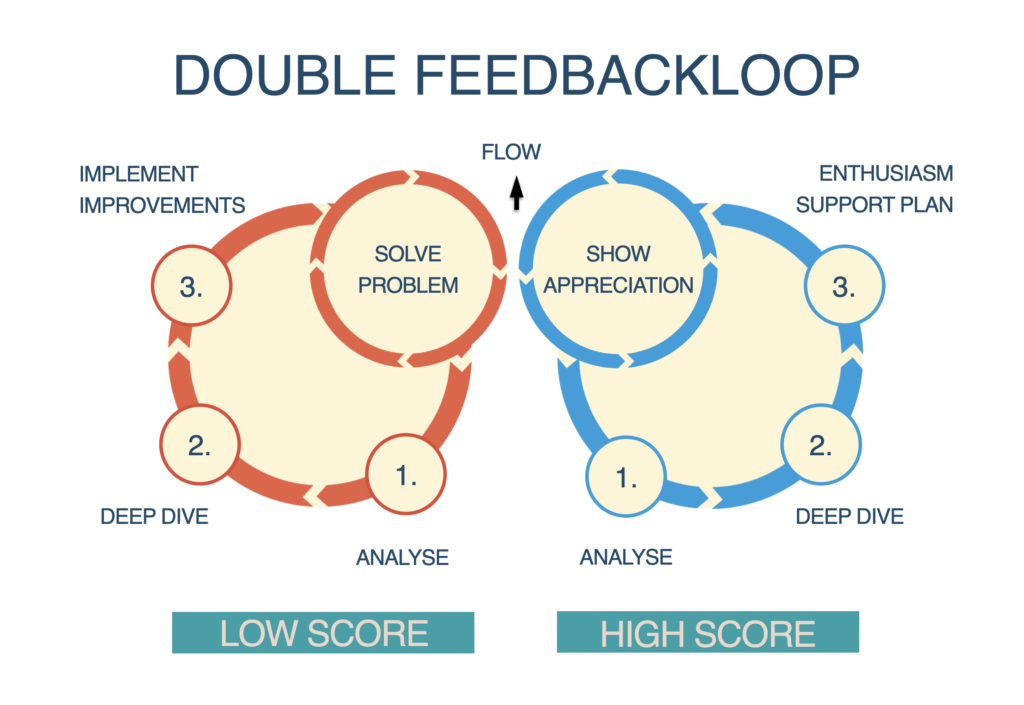

Another application relates to the set-up of an organisation. By converting negative feedback systems to double feedback loops, not only are problems identified, but also aspects that are going well. Figure 1 is a representation of a double feedback loop in the context of customer research. This ensures that special achievements receive attention and positive customer stories are collected. It provides powerful fuel to ignite enthusiasm in an organisation and has been shown to create a positive work environment in practice.

Figure 1

Interventions concerning customer and employee enthusiasm not only lead to more intrinsic motivation in employees, but also show positive effects at the organisational level. To complete the Superpromoter Academy, the course participants have to put the theory into practice within their own organisation and provide feedback. This creates a good picture of the activities deployed. Some have organised activities to activate enthusiasm within their department or to promote collaboration with other departments on the basis of this theme. Others have invited enthusiastic customers or organised a day for management with the theme of enthusiasm. Approximately 250 employees at the Volksbank took part in the training (14 courses). During this period, the NPS (a measure of customer enthusiasm) increased from -65 to 0 and the eNPS (a measure of employee enthusiasm) from -33 to +35. These results were not achieved through training alone, but according to the management of the Volksbank at the time, the intervention did make a significant contribution. Several training courses have also been held at companies such as NUON, Nationale Nederlanden, Rabobank and DTG, and employees have developed many activities to stimulate enthusiasm within the organisation. Training courses and workshops were held for Philips in the Netherlands and India. “The enthusiasm of customers that I was able to give back to the organisation does a tremendous amount of good and at the same time sets more in motion.” Patrick Lerou, Senior Manager Philips Health Care.

In conclusion: enthusiasm, passion and success

We live in a world where enthusiasm and passion are becoming increasingly important. That is because there is a clear relationship with happiness in life, but also out of economic necessity. When the vast majority of the workforce still worked in the fields or on assembly lines, it was less important that employees were passionate about their work. In the current labour market, there is a need for creativity, flexibility and initiative. This trend will continue further due to automation and robotisation. Employees only function well in an environment like this if they are intrinsically motivated. In addition, it is increasingly important for organisations to be customer-oriented. In fact, the most successful organisations today know how to get customers so excited that they spread their enthusiasm and bring in other customers. Google, Facebook, Airbnb and TESLA didn’t get to where they are today through advertising, but because customers spread their enthusiasm by word of mouth or “word of mouse”. This can only be achieved with enthusiastic and passionate employees. I would like to see these themes given more attention in positive psychology – in the interest of employees, organisations and society in general.

This article was published in the Dutch Journal of Positive Psychology (Tijdschrift voor Positieve Psychologie).

Bibliography

Vallerand, R. J., & Houlfort, N. (2003). Passion at work: Toward a new conceptualization. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on values in organizations, 175-204. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Vallerand, R.J., Verner-Filion, J. (2013). Making People’s Life Most Worth Living: On the Importance of Passion for Positive Psychology. Terapia psicolÓgica, 2013, Vol. 31, No 1, 35-48.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991) Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial.

Reichheld, F. (2003) ’The One Number You Need to Grow’, in: Harvard Business Review, Dec. 2003, 46-54.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Ferrara, E. Yang, Z. (2015). Measuring Emotional Contagion in Social Media, journal PLOS One.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper Perennial.